Accokeek Creek (18PR8)

The Accokeek Creek site (18PR8) was a major Indian town located on the Potomac River about

midway between Piscataway and Accokeek creeks in Prince George's County, Maryland. The site

was excavated between 1935 and 1939 by Alice L.L. Ferguson, an avocational archaeologist who

discovered the site soon after she purchased the property in 1923. Mrs. Ferguson's investigations

were extensive and revealed a large complex of consecutive palisades, post molds, hearths, refuse pits,

dog burials, and ossuaries across an area measuring roughly 650 by 350 feet. Mrs. Ferguson identified the

site as Moyaone, a settlement visited and mapped by Captain John Smith in 1608, although some archaeologists

now question that interpretation. Thousands of artifacts, including lithics, ceramics, and other

objects were recovered during the excavations and indicate that the town at Accokeek Creek, whether

it was Moyaone or not, was a major center on the Potomac River.

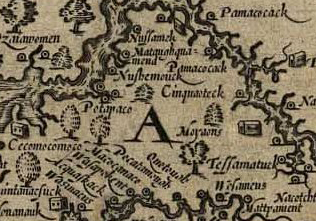

Portion of Smith map showing Moyaone (or "Moyans").

Portion of Smith map showing Moyaone (or "Moyans").

Materials from the Accokeek collection are stored in at least four places, including the Smithsonian

Institution, the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology at the University of Michigan, the Maryland

Archaeological Conservation Lab, and the National Park Service's Museum Resource Center. The collection

examined for this project was the one housed at the University of Michigan, where the collection has

resided since the 1950s. There, the collection is organized into two parts, including NAGPRA and

non-NAGPRA materials. The non-NAGPRA collection was studied and photographed as part of this project.

Unfortunately, provenience information appears to have been lost for the material. Further, the material

from Accokeek Creek and the Susquehannock Fort site, both designated 18PR8,

appears to have become mixed; if so, it is not possible at this time to separate the material.

Archaeological Investigations

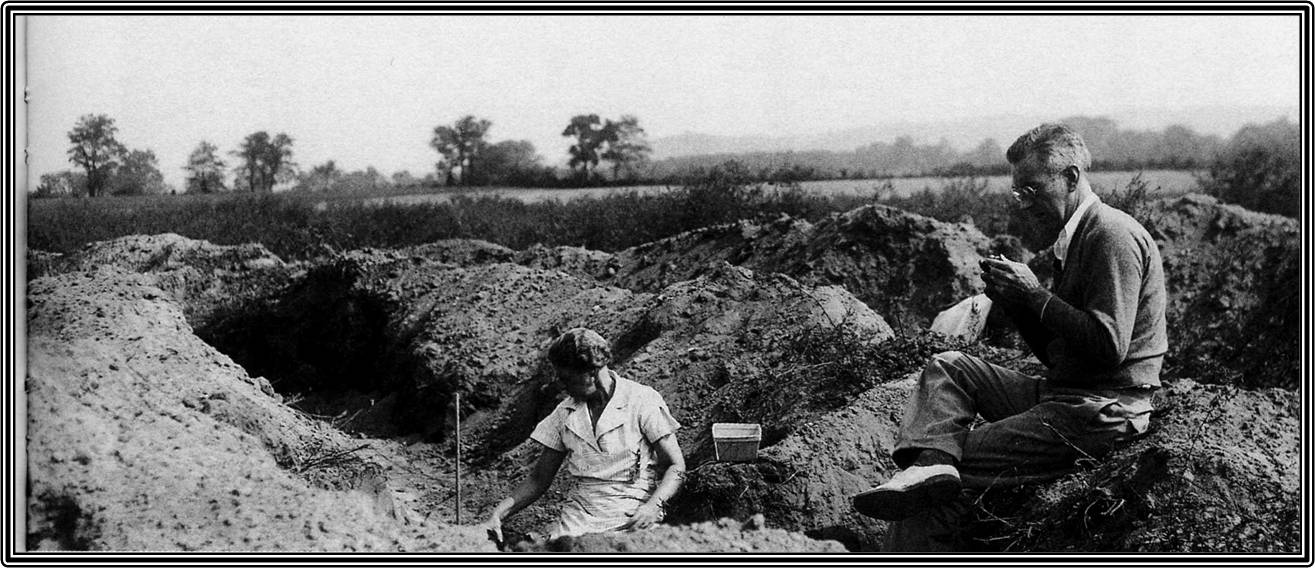

Alice Ferguson excavating the site. Photo courtesy Alice Ferguson Foundation.

Alice Ferguson excavating the site. Photo courtesy Alice Ferguson Foundation.

Mrs. Ferguson began her excavations in 1935 and managed to expose large sections of ground between

then and 1939. She used school boys and farm workers to hand-strip the overlying plow zone level;

no deposits were screened. A grid laid out in 50-foot sections was put in place and these sections were

subdivided into 5-foot squares as excavation proceeded. When a feature was encountered, "every pit was

cross sectioned and diagrammed and all but a few of the very small pits were photographed." Some effort

was made at the time to retain provenience information, for the plow zone (or what Mrs. Ferguson described

as the topsoil) as well as for the features. "All artifacts found in the pits," Mrs. Ferguson later wrote,

"were kept and recorded separately but those found in the topsoil in stripping back the refuse mantle were

merely given the number of the section in which they were found."

Features included a large number of post molds distinguished by their darker color, straight sides,

and finished (tapered or blunt) ends, located anywhere from 4 to 24 inches below the plow zone. Many dozens

of post molds measured approximately 2 inches in diameter. Post molds for the "stockades" or palisades were

larger and more robust.

The post molds forming the palisade lines were reported to be evenly spaced at intervals of about one foot

with molds ranging in diameter from 2 to 8 inches with most 4 inches or larger. Mrs. Ferguson identified

14 iterations of palisade lines, some of which were contemporary while others were of different generations.

Other features included refuse pits, many of which follow what Mrs. Ferguson called the "I stockade,"

one of the outermost palisades. Most of the refuse pits ranged between 2 and 2.5 feet in depth below

plow zone. A few, including Pits 42, 53, and 55, extended 4 feet into subsoil. Pit 55 yielded 3,546

ceramic fragments, 1,492 deer bone fragments, 201 turtle carapaces, 112 sturgeon bones, one complete

dog skeleton and other dog bones, 27 raccoon bones, 45 worked bone fragments, 19 awls, 11 pipe fragments,

28 projectile points, one shell bead, one human skull, and "a great many unidentified" bones.

Hearths, or what Mrs. Ferguson called fire pits, measured 1 to 1.5 feet in diameter

and extended up to 18 inches below the plow zone.

Mrs. Ferguson also defined storage pits but how they differed from the refuse pits is unclear.

"There were many small pits, larger and deeper than the first pits, and without any traces of

fire." They were 2.5 feet deep below the plow zone.

Traces of "irregular discolorations of the [soil] suggesting the decay of vegetable matter"

may have led Mrs. Ferguson to interpret these features as storage pits.

Mrs. Ferguson also observed what she described as stone piles with their tops truncated.

These stone piles ranged in size from as small as "a handful" to two outside the town

measuring 8 and 12 feet, respectively, in diameter. They were "abundant near burial pits

and ossuaries" and Mrs. Ferguson suggests they could be the "altar stones they call

Pawcorances" observed by Captain John Smith.

Mrs. Ferguson also excavated a number of human burials, including individual, small group,

and large ossuary interments. Four ossuaries were found at the Accokeek Creek site and one

at Mockley Point. The ossuaries at Accokeek Creek contained at least 1,438 individuals.

Curry (1999) has reviewed and summarized the findings from Ferguson's work. Generally, it

has not been possible to reconstruct the nature of the burials—that is, whether they were

extended, flexed, or bundled, except in a very few cases. No European artifacts were recovered

in association with the ossuaries, although copper and shell beads, Indian ceramics

(including one whole large and two whole small pots), a few tobacco pipe fragments, and stone

triangles were recorded in association with the burials.

Artifacts

Because of the nature of both how the site was excavated and how it was curated in the middle

and later decades of the 20th century, provenience information that may have existed has become separated

from the artifacts reexamined as part of this project. All artifacts are, therefore, assigned a

single, general context (1). The artifacts found in the database come from tables found in Robert

L. Stephenson's 1963 report on Mrs. Ferguson's work at the site.

Stone artifacts form 6,512 objects, including projectile points (n=4,138), cores (n=1,207),

scrapers (n=623), pigments (n=108), drills (n=73), gorgets (n=53), hammerstones (n=48), manos

(n=30), net weights (n=26), axes (n=20), celts (n=20), pestles (n=17), beads (n=8), smoking pipes

(n=7), abraders (n=7), boatstones (n=7), choppers (n=6), grinding stones (n=6), stone ornaments (n=5),

mauls (n=2) bannerstone (n=1), and unidentified stone objects (n=101). The lack of lithic debitage

in the collection suggests that either Mrs. Ferguson did not keep these materials or they were removed

from the collection somewhere along the way. There is little doubt, however, had these artifacts been

kept, they would have numbered in the thousands.

Significantly, a number of stone artifacts recovered from the Accokeek Creek site appear to be manufactured

from European flint. At least one triangular point of European flint is included in the collection. It is

possible that this point is associated with the later nearby ca. 1675 occupation of the Susquehannock Fort.

In general, however, the majority of artifacts do not seem to be materials associated with the fort's occupation,

at least not based on Mrs. Ferguson's writings. How these artifacts of European flint came to the Accokeek Site

is somewhat mysterious.

Projectile points suggest occupation in the site's vicinity since at least the Late Archaic. Identified

projectile point types include Piscataway (4850-3750 BC), Vernon (possibly Halifax, 4350-3600 BC), Brewerton

(4300 BC-1600 BC), Bare Island (3750 BC-600 AD), Clagett (3700-2450 BC), Calvert (1200 BC-200 AD), Rossville

(500 BC-300 AD), and Steubenville (possibly Selby Bay/Fox Creek, 200-900 AD). These identifications, however,

use Stephenson's identifications, and type descriptions have changed in the decades since Stephenson completed

his study. Triangular points, considered later in date, are also included in the collection, although the numbers

are not large. Clearly, the projectile points suggest a use of the site for centuries, beginning perhaps as

early as 6,000 years ago.

Ceramic artifacts include 420 clay tobacco smoking pipe fragments and 58,298 vessel fragments. The collection

includes a number of almost whole vessels, or vessels complete enough and for which the form can be identified.

Well over half of the ceramic collection consists of Potomac Creek wares (n=34,788), including plain and

cord-marked varieties. The remaining ceramics suggest an occupation of the settlement at Accokeek Creek

for at least several centuries, stretching back to the Early Woodland. Surprisingly, however, no fragments

of steatite bowls were recovered from the site, or at least they are not found in the collection.

Other artifacts include shell beads (n=4,024), bone beads (n=18), bone awls (n=383), bone "bodkins" (n=18),

bone projectile points (n=15), bone pins (n=23), turtle shell ornaments (n=29), bone utensils (n=4), and bone tools.

References

Curry, Dennis C. 1999. Feast of the Dead: Aboriginal Ossuaries in Maryland. Crownsville:

Maryland Historical Trust Press.

Dent, Richard J., and Christine Jirikowic. 2000. Accokeek Creek: Chronology, the Potomac Creek Complex,

and Piscataway Origins. Paper presented 67th Annual Meeting of the Eastern States Archaeological Federation, Solomons, MD.

Ferguson, Alice L.L., and Henry G. Ferguson. 1960. The Piscataway Indians of Southern Maryland. Accokeek, MD:

Alice Ferguson Foundation.

Ferguson, Alice L.L., and T. Dale Stewart. 1940. An Ossuary Near Piscataway Creek, a Report on the

Skeletal Remains. American Antiquity 6(1):4-18.

Stephenson, Robert L., and Alice L.L. Ferguson. 1963. The Accokeek Creek Site: A Middle

Atlantic Seaboard Culture Sequence. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers 20, Ann Arbor.

What You Need To Know To Use This Collection

The Accokeek Creek collection was formed in the mid- to late 1930s and is stored in at least two

locations, including the Smithsonian Institution and the Museum of Anthropology at the University of

Michigan. Only the non-NAGPRA materials curated at the University of Michigan were reexamined for

this project. While provenience information was reported to have been collected during excavations,

the information appears to have become permanently separated from the majority of artifacts found in

the collection at Michigan. It is also likely that materials from both the Accokeek Creek and

Susquehannock Fort sites have become mixed. The collection was not formally cataloged until the

early 1960s, and the catalog used for the Colonial Encounters project comes directly from Stephenson and

Ferguson's (1963) book. If paper catalogs exist, they were not found during this effort (although a file

cabinet with paper files was found at Michigan but was not made available for review). Finally,

it is possible that materials reported in the collection in 1963 have been lost or misplaced

in the ensuing years.

Further Information About the Collection

The Accokeek Creek collection is owned and curated by the University of Michigan's Museum of Anthropological

Archaeology. For more information about the collection and collection access, contact the Collection

Manager, at 734-763-0655; email ummaa-collection-mgr@mich.edu.

To Download Data

Data and a variety of other resources from this site are available for download. To download data,

please go to the Downloads page.