Posey (18CH281)

Introduction

The Posey Site (18CH281) is located near Mattawoman Creek in Charles County,

Maryland, aboard what is now the Naval Surface Warfare Center–Indian

Head Division. The site was initially identified in 1963 by Navy chemist

Calvert Posey in an area that had been damaged by an earlier explosion

at Indian Head’s Biazzi Nitration Plant, where nitroglycerin was manufactured.

In 1985, the site was tested by William Barse as part of a much larger

archaeological survey of the Indian Head facility. The site was investigated

more extensively in 1996 by staff from Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum,

under the direction of Julia A. King and Edward E. Chaney.

Artifacts recovered from the Posey Site indicate the presence of a small,

single-occupation component, probably Native American, dating to the period

between 1650 and 1700, although the exact size of the original settlement

is uncertain because portions of the site were destroyed by later construction.

Systematic shovel testing around the site suggests that, unlike the

Camden Site (44CE3) on the south side of the

Rappahannock River, the Posey Site was a relatively isolated domestic settlement,

although other Native American occupations are no doubt present in the area along

Mattawoman Creek that was reserved for Indian use in the 17th century.

Historical research suggests that the Indians living at Posey were likely

Mattawoman, a component group of the Piscataway

Indians. The land containing the site had been granted by Lord Baltimore

to Thomas Cornwallis in 1636, and was re-patented by Cornwallis in 1654,

although there is no evidence any Europeans were living in the area by

that time. In October 1665, Nancotamon, one of the great men of Mattawoman,

came before the Maryland Provincial Council and asked what his people should

do, whether they should “remove further into the woods or to remayne upon

the land where they now or lately lived,” presumably in this portion of

Charles County. In response, the Council ordered the metes

and bounds of the “ould habitations” of the Mattawoman surveyed,

and, in the interest of peace and safety, forbade any Englishman from taking

up lands within those boundaries. The Council further declared that any

Englishman so settling risked imprisonment.

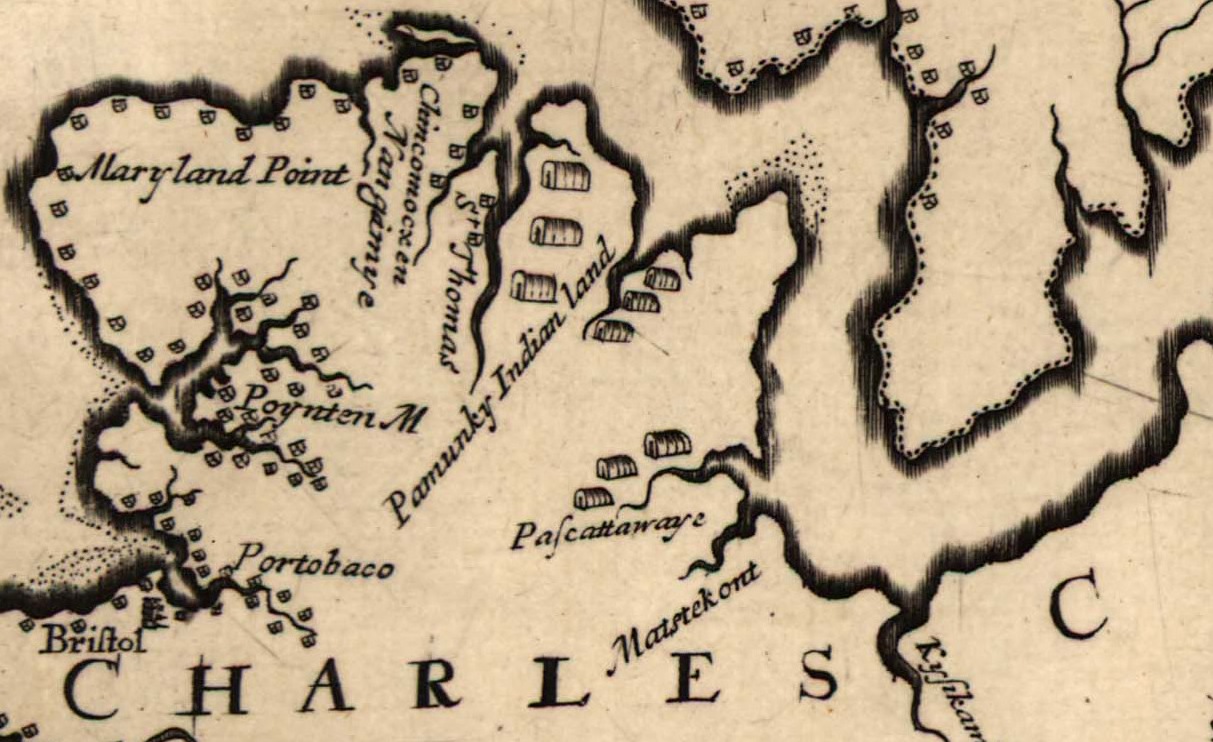

Portion of Hermann map

Portion of Hermann map

For the next several years, the English government worked toward protecting

Indigenous lands in this area. In particular, the Provincial Council forbade

settlement between the heads of Mattawoman and Piscataway creeks until

portions of the lands had been officially allotted to the Mattawoman. Significantly,

this is the area including the Posey site. Augustine Herman’s map of Maryland

and Virginia, which was completed in 1670 and published in 1673, shows three longhouse

structures in the vicinity, although not in the exact location of the Posey

site. Significantly, Herman’s map also shows encroaching English settlements

on the south side of Mattawoman Creek. Researchers have cautioned that

Herman’s map, while impressively accurate, should not be taken literally.

Still, the map does suggest English settlement very nearby at the end of

the third quarter of the 17th century.

Following Cornwallis’ death in the late 1670s, his land was willed to his

wife, Penelope. The widow Cornwallis sold Mattawoman Neck in 1688 to Captain

Edward Pye. One of the instruments of transfer recognizes that the land

was “now in possession of Indians.” Although twenty-five years previously

the Provincial Council had made concerted efforts to protect Indigenous settlements

in this area, such issues do not seem to have been a concern when Pye acquired

the land. Nonetheless, the Indians living on the tract may have been left

alone, at least for a while. In 1695, the colonial government pondered

how it might convince Indigenous people living in that area to allow some English

settlement, thereby increasing the production of tobacco.

It is about this time—the end of the 17th century—that the

Posey site appears to have been vacated.

Archaeological Investigations

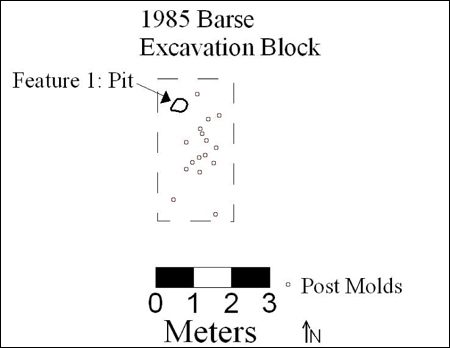

Barse excavation block.

Barse excavation block.

Following the site’s discovery in 1963, Calvert Posey and his colleagues

excavated a large number of artifacts from it. They uncovered a number

of features, including house patterns and storage pits, at least some which

were apparently excavated. A brief report by Posey (n.d.) describes—without

quantifying—some of the artifacts he found, including Native and European

pottery, red and white clay pipes (including one he claims bore a 1618 date

mark), copper and stone triangular points, iron nails, lead shot, shell

beads, and large amounts of wild animal bone. No field maps or notes on

this work are known to exist. The collections from this effort remain in the

possession of the Posey heirs.

In 1985, William Barse excavated a total of 11.5 square meters, including a block

excavation measuring 4 by 2 meters and three additional units. At the base

of plow zone in the block excavation, Barse recorded 17 features, including

16 post molds and a small pit. Several features were tested. Barse concluded

that the Posey Site was first occupied by Indigenous people just prior to

the arrival of Europeans, and continued to be occupied for an unknown period

of time following the English settlement of Maryland. The overwhelming

majority of recovered artifacts included materials produced by Native Americans,

although a small amount of European material was also recovered. Barse

interpreted these European artifacts as trade goods.

Excavation units and 1985 excavation block photographed facing northeast, showing possible filled ravine head

(Courtesy Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Naval District Washington)

Excavation units and 1985 excavation block photographed facing northeast, showing possible filled ravine head

(Courtesy Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Naval District Washington)

Excavation units photographed facing south showing amorphous

midden feature (Courtesy Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Naval District

Washington)

Excavation units photographed facing south showing amorphous

midden feature (Courtesy Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Naval District

Washington)

Julia King and Edward Chaney returned to the site in 1996 in an effort to identify the

spatial and chronological boundaries of the site as precisely as possible,

and to collect evidence useful for interpreting Indian lifeways in 17th-century

Maryland. A total of 510 shovel tests were excavated at intervals of eight

meters over an area measuring approximately 9.9 acres. Fill from the shovel

tests was screened through ¼-inch hardware cloth. Thirty-seven 1.5-by-1.5-meter

units were subsequently excavated within the boundaries of the site as

established by the shovel testing. The plow zone from these units was screened

through ¼-inch mesh. A 25-by-25-cm column sample was taken from

each unit and water-screened through fine mesh in an effort to recover

beads and other small artifacts and faunal remains.

Seven discrete features, including five post molds, a pit, and an unidentified

feature, along with one large midden deposit, were identified below the

plow zone. The post molds were mapped, sectioned, excavated, and the profiles

recorded, all suggesting posts driven into the surrounding subsoil. The

large midden feature was linear in places and amorphous in others, and

may represent the head of a ravine used to discard refuse. Eight sections

were excavated in an effort to document the feature’s shape, stratigraphy,

and artifact content. Most of these sections were water-screened, although

several samples were retained for flotation. The feature’s fill contained

a rich assemblage of cultural material, including artifacts of Indigenous and

European manufacture. The feature itself was relatively shallow (10 to

20 cm in depth) with a sloped, basin shaped bottom.

Louis Berger and Associates conducted additional testing at the site in 2012,

including the excavation of one test unit in the site core and 43 shovel tests

on the north side of Braggs Road, none of which were positive. Materials recovered

from the Berger work are not included in the database.

Artifacts

More than 11,000 materials, including artifacts, shell, and animal bone,

were recovered during the 1996 investigations, from both shovel tests and

excavation units. Slightly more than 1,500 objects are included in the

collection that were generated by the excavations undertaken by Barse in 1985. Among

these artifacts are Indigenous and European ceramics, red and white

clay tobacco pipe fragments, glass, lithic tools and debitage, nails and

other metal objects, bone, shell, and relatively large numbers of materials

apparently related to Navy construction activities and the Biazzi Plant

explosion.

Ceramics include nearly 3,000 fragments of Native-made ceramics, predominantly

Potomac Creek wares, although small amounts of Yeocomico, Camden, Moyoane,

and Accokeek ceramics are also present in the collection. More than

90 percent of the Potomac Creek fargments are of the plain variety, suggesting

a 17th-century date of manufacture. At least 47 Potomac Creek vessels are

represented in the collection. Wheel-thrown ceramics of European manufacture

number less than 70 fragments, represented primarily by tin-glazed earthenware.

Other European types present include Rhenish brown stoneware, Rhenish blue

and gray stoneware, black lead-glazed earthenware, and five fragments of Challis-like

earthenware.

Both Native-made and European white clay tobacco pipe fragments were recovered

from the site, although in small numbers when compared with contemporary

sites occupied by the Chesapeake English. All of the red tobacco

pipe fragments appear to derive from hand-made, Native-type smoking pipes.

Lithic artifacts include tools, debitage, and fire-cracked rock. Stone

types include quartz, quartzite, chert, rhyolite, and European flint. Indeed,

while quartz was the most common stone type at approximately 63 percent,

European flint formed 18 percent of the lithic assemblage. Much of this

flint consisted of debitage, although two gunflints and a cutting tool

were made of European flint.

Thirty-eight copper alloy fragments were recovered from the site, including

triangles, rolled cones, and scraps or fragments. At least one of these

triangles was clearly intended as a projectile point, made of two layers

of metal with a deep basal notch terminating in a round perforation near

the artifact’s center. The remaining five triangles were flat, and two

had perforations in their centers. They too may have functioned as points,

although an ornamental usage may also be suggested. Two copper alloy

cones were also recovered.

Lead or pewter artifacts include several pieces of shot, a hemispherical

button, and a tongue-shaped piece of lead sheet identified as possibly

a pad to help secure a gunflint within the lock of a musket or other firearm.

A small fragment of possible lead sprue and a small unidentified cylindrical

object were also recovered.

Iron artifacts include nails and nail fragments, a knife blade, a possible

furniture or architectural fragment, and numerous pieces of unidentified

iron. Seventy-nine wrought nails or nail fragments were recovered, all

in advanced stages of deterioration. Two nails appear to have been deliberately

clinched, which suggests that these artifacts had been driven into boards

and then bent or folded over for extra holding power and safety.

A buckle fragment of unidentified metal was also recovered.

Glass artifacts include colonial bottle fragments (including two nearly

complete case bottle kick-ups), three beads, and four buttons with remnant

metal shanks. One of these buttons has a white, star-shaped white glass

inlay on its upper surface, and is identical to buttons recovered from

the Burle's

Town Land Site (18AN826). A similar button is depicted in a

mid-16th-century portrait of an English woman, but it is unclear if the

button recovered from the Posey site was used by the site's occupants as a

clothing fastener.

Bone artifacts include fragments of a bone comb and a bone needle fragment.

The bone comb pieces come from the same object. A relatively large number

of tubular (peake) and disk (roanoke) shell beads were also recovered from

the site as a result of the effort to collect and water-screen column samples

from the plow zone. Several bead blanks provide evidence that shell beads

were probably being manufactured on site.

Although the animal bone recovered from the Posey Site was considerably

fragmented, and much of it had been recovered from plow- and Navy-disturbed

contexts, samples were submitted for zooarchaeological analysis. David Landon

fount that the assemblage contains a wide range of species representing many

of the resources in the rich environment of the Chesapeake Bay

estuary—fish, shellfish, aquatic and land turtles, terrestrial mammals

(especially deer), and semi-aquatic mammals. However, bird bones are absent

from the assemblage. When compared with faunal assemblages recovered from

pre-1600 Indigenous sites, the Posey site faunal assemblage is similar to

these collections—aquatic and terrestrial mammals, turtles, and fish,

but few birds. When compared with assemblages recovered from contemporary

sites occupied by the Chesapeake English, however, the differences are

striking. The only European domesticate in the assemblage consists of a few

small fragments of pig bone, an animal that could have been easily acquired

through trade or retaliation for crop damage.

Grace Brush of Johns Hopkins University collected and analyzed two soil

cores from Mattawoman Creek near the site. Both were as interesting for

what they did not reveal about the site as much as for what they suggested.

Both cores were dominated by pine and wetland species, and there was no

distinction between pre- and post-colonial vegetation, as has been seen

in other areas. There was no evidence of deforestation or other effects

on wetland species caused by European agricultural practices, even in the

later 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. In part this may be due to the difficulty

of distinguishing ragweed from marsh elder pollen; still ragweed (or marsh

elder) pollen is present throughout these cores, the dates of which range

back to approximately the mid- to late 14th century.

References

Barse, William P. 1985. A Preliminary Archaeological

Reconnaissance Survey of the Naval Ordnance Station, Indian Head, Maryland,

Volume I: Cornwallis Neck, Bullitt Neck and Thoroughfare Island. Draft

report prepared for the Department of the Navy, Chesapeake Division, Naval

Facilities Command.

Brush, Grace S. 1997. Pollen Study of Two Sediment

Cores from Mattawoman Creek, Maryland. Prepared for the Department of Research,

Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum, St. Leonard.

Galke, Laura J. 2004. Perspectives on the Use of European

Material Culture at Two Mid-to-Late 17th-Century Native American Sites in the

Chesapeake. North American Archaeologist 25(1):91-113.

Harmon, James M. 1999. Archaeological Investigations

at the Posey Site (18CH281) and 18CH282, Indian Head Division, Naval Surface

Warfare Center, Charles County, Maryland. Draft manuscript on file, Maryland

Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum,

St. Leonard.

Katz, Gregory, and Charles LeeDecker. 2012. Phase I Survey

for Riverwater Line Replacement at the Posey Site (18CH281), Naval Support

Facility Indian Head, Charles County, Maryland. Ms. on file,

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, Jefferson Patterson Park

and Museum, St. Leonard.

Landon, David B., and Andrea Shapiro. 1998. Analysis

of Faunal Remains from the Posey Site (18CH281). Prepared for the Department

of Research, Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, Jefferson

Patterson Park and Museum, St. Leonard.

Posey, Calvert R., Sr. n.d. Matiwataquamend: An Indian

Village on the Indian Head Peninsula of the Mattawoman Creek. Ms. on file,

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, Jefferson Patterson Park

and Museum, St. Leonard.

What You Need To Know To Use This Collection

- The Posey site was occupied from c. 1650 until 1690.

- The site was discovered during a chemical explosion.

- Excavations were undertaken at the site in 1985, 1966, and 2012.

- Efforts were made in 1996 to use the 1985 grid. No points were left behind

in 1985 so the grid fit is approximate.

- Materials from the 2012 excavations are not included in the database.

- Plow zone was recovered and screened through 1/4-inch mesh and window

screen.

Further Information About the Collection

The Posey Site archaeological collection is owned by the U.S. Navy and

curated by the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory. For more

information about the collection and collection access, contact Sara Rivers Cofield,

Federal Collections Manager, at 410-586-8589;

email Sara.Rivers-Cofield@md.gov.

To Download Data

Data and a variety of other resources from this site are available for download. To download data,

please go to the Downloads page.