Susquehannock Fort (18PR8)

Introduction

Located at Mockley Point on Piscataway Creek, the Susquehannock Fort site (18PR8) bears witness

to a bloody chapter in Anglo-Native relations.

In 1674, a group of Susquehannocks, then at war with the Five Nations Iroquois, sought refuge in

Maryland. Governor Charles Calvert agreed to their relocating provided they constructed their

new settlement above the Potomac falls. Instead, the Susquehannock erected their fort in an

abandoned fort on Piscataway Creek, perhaps intending to seek the protection of the nearby

Piscataway.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Potomac in Virginia, a group of Doeg Indians were seeking

revenge on Thomas Mathews after he had cheated them in some transaction. The situation in

Virginia escalated with the deaths of both Doegs and Mathews's son and servant, and the Doegs

fled into Maryland. A group of Virginians led by Colonel George Mason pursued the Doegs into

Maryland and confronted them in a group of cabins, presumably at the Susquehannock Fort.

Evidently the Doegs had taken shelter there.

Colonel Mason and his allies ended up killing several Doegs, taking the leader's son hostage,

and then open firing on Indians fleeing a second cabin. These Indians were not Doegs but

Susquehannocks, and 14 were killed during the skirmish.

Not surprisingly, the Susquehannocks retaliated for this indiscriminate action, and now the

two governments were forced to take action against a group Indigenous communities when they

had been at peace. Colonel John Washington (great-grandfather of George) and Major Isaac

Allerton of Virginia and Major Thomas Truman of Maryland besieged the Susquehannocks in

their fort at Piscataway Creek. The Marylanders led a force of 250 men with support from

the Piscataway—an event that would hound the Piscataway for almost a decade.

During the siege, the Susquehannocks sent out five of their Great Men for a parley with

the English. The Susquehannocks blamed the Seneca for the recent raids and produced a

medal and articles of peace given to them by the Maryland government. Without provocation,

the English troops executed the Indians during the parley.

For the next six weeks, the Susquehannocks remained besieged within their fort, still managing to,

under cover of darkness, kill 50 English men and a number of horses, the latter for food.

Finally, the remaining Susquehannocks escaped the siege during the night and

proceeded to retaliate, raiding the frontier English plantations primarily

in Virginia. When Governor Berkeley rejected their peace overtures, their raids on the

Virginia frontier continued, precipitating Bacon's Rebellion in 1676.

Archaeological Investigations

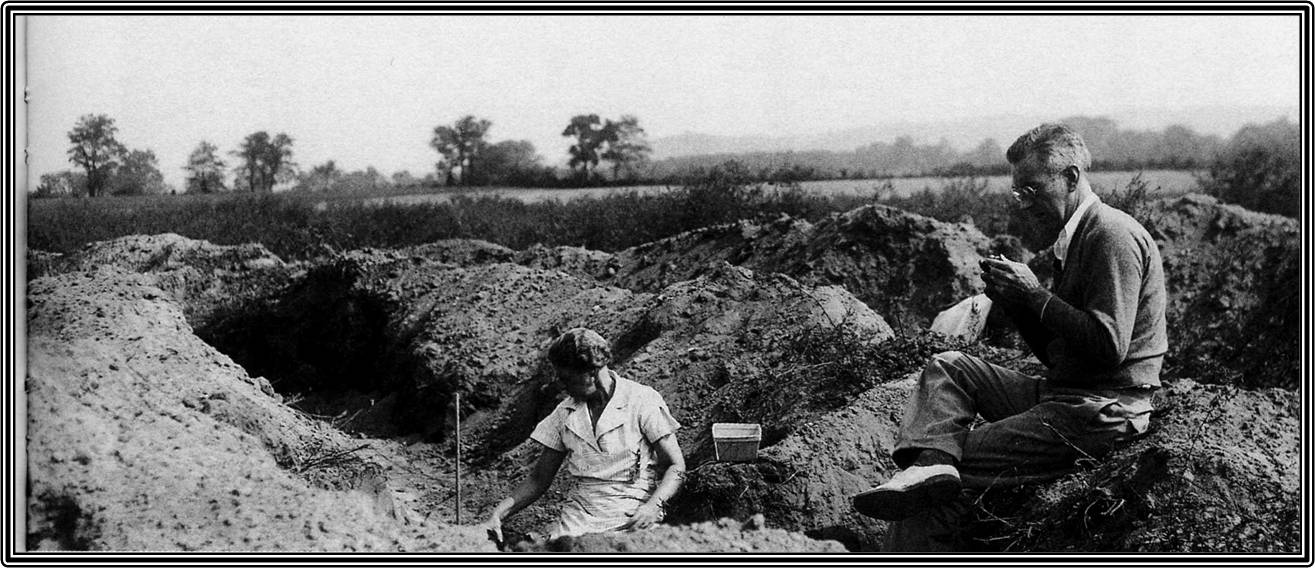

Alice Ferguson excavating the Accokeek Creek site.

Alice Ferguson excavating the Accokeek Creek site.

The Susquehannock Fort site was excavated by avocational archaeologist Alice L.L.

Ferguson between 1939 and 1940. By and large, excavation methods were similar to

those employed at Accokeek Creek.

Inconsistencies in Mrs. Ferguson's descriptions of methods and features are partially

delineated in Curry (1999).

The first excavations at the fort site at Mockley Point were undertaken in 1939.

During this season, Mrs. Ferguson and Professor Thomas Wertenbaker of Princeton University

located the site at Mockley Point with the assistance of a colonial map and aerial photography.

In 1940, Mrs. Ferguson led a second season of excavation, during which she and her team uncovered

stockade post molds showing evidence of burning (Ferguson 1941:8). That same year, Mrs. Ferguson

uncovered an ossuary containing 42 burials, a staggering number given the Susquehannock Fort's

length of occupation (about a year) and meager population size (estimates place the number at

around 500 individuals). The remains recovered were later examined by Ales Hrdlicka and T. Dale

Stewart, physical anthropologists at what was then called the National Museum (now the Smithsonian

Institution). Included in the ossuary were seven young children and four syphilitic adults. In her

1941 report, Mrs. Ferguson noted that the Mockley Point ossuary was atypical in its equal ratio of

skulls to long bones. Mrs. Ferguson also excavated a small pit containing a number of trade goods,

located about a foot away from the ossuary.

Perhaps the most impressive feature recovered during Mrs. Ferguson's excavations of the Susquehannock

Fort was the fortification's plan: palisades set in a square with what appear to be square bastions

at the two surviving corners (about 1/3 of the fort has been lost to erosion in 1941). If

photographs survive of the fort's plan, they have not been published. While Mrs. Ferguson's drawing

no doubt has smoothed the variability of the archaeological record, her representation of the

Susquehannock Fort provides important evidence about the nature of fort-building at the end of

the first century of colonization in British North America.

Mrs. Ferguson's drawing provides an important comparative resource for a drawing that survives in the British

Public Records Office of the fort while it was under siege. This drawing suggests that the fortification

was surrounded by a second enclosure, perhaps of brush, and all of this was found within an encircling

ditch. Had the site been located and tested at the end of the 20th century, there is no doubt that features

invisible to Mrs. Ferguson would have been seen by modern archaeologists.

Artifacts

Considering the Susquehannock refugees inhabited the site for only eighteen months, they left behind a

good deal of archaeological material. The diverse collection of artifacts recovered from the ossuary

alone may reveal information about Susquehannock involvement in 17th-century trade. Among these were

"three Jew's harps, seven copper hawk bells, eight iron brackets, an iron hoe, a copper finger ring

set with glass, a snuff box, fragments of a pair of scissors, and a flattened lead musket ball"

(Ferguson 1941). In addition, two tobacco pipes (one white clay and a second later identified as Susquehannock)

were recovered from the deepest contexts of the ossuary (Curry 1999). Trade was also evidenced in the

small cache of artifacts recovered from a pit near the ossuary. Recovered from this pit were "two

iron hoes, an upright Dutch gin bottle, two small iron pots and a mass of almost completely disintegrated

stuff that looked as though it might have been textile" (Ferguson 1941:9). Mrs. Ferguson interpreted

this cache as either a hastily stashed "treasure pit" or a ritual offering associated with the ossuary.

None of the artifacts described by Mrs. Ferguson are found in the database. These materials, now owned by

the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology at the University of Michigan, are subject to rules adopted by

the museum to meet requirements under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

The Susquehannock Fort collection and with the Accokeek Site collection were both given to the University

of Michigan in the 1950s. For the Accokeek Creek site collection, provenience information appears to have

been lost. It is possible that some of the Native-made material in the Accokeek Creek collection came

from the Susquehannock Fort site, especially given that both designated 18PR8, have been combined.

There are a number of artifacts in the Accokeek Creek collection that appear to be made from European flint.

It is very possible that these objects are associated with the late 17th-century fort.

References

Curry, Dennis C. 1999. Feast of the Dead: Aboriginal Ossuaries in Maryland.

Crownsville: Maryland Historical Trust Press.

Ferguson, Alice L.L. 1941. The Susquehannock Fort on Piscataway Creek. Maryland

History Magazine 36(1):1-9.

Rice, James D. 2012. Tales from a Revolution; Bacon's Rebellion and the Transformation

of Early America. New York: Oxford University Press.

What You Need To Know To Use This Collection

- The Susquehannocks occupied the fort between c. 1674-75.

- The Susquehannock Fort collection has been combined with the Accokeek collection at the Museum of

Anthropology at the University of Michigan. Therefore materials are included in the database

in 18PR8 (the Accokeek collection).

- Researchers are directed to Mrs. Ferguson's 1941 article for additional detail.

Further Information About the Collection

The Susquehannock Fort collection is owned and curated by the University of Michigan's Museum of

Anthropological Archaeology. For more information about the collection and collection access,

contact Lauren Fuka, Collection Manager, at 734-763-0655 or by email at lfuka@umich.edu.

To Download Data

Data and a variety of other resources from this site are available for download. To download data,

please go to the Downloads page.